How a currency devaluation in Kazakhstan made the country’s poor worse off – News

This article, written by Anatoli Colicev, Chair in Marketing, Strategy and Analytics, in our Management School, Joep Konings, Dean of the Graduate School of Business, Nazarbayev University, and Joris Hoste, Research Fellow in the Department of Economics, KU Leuven was originally published in The Conversation:

It is the job of the government to keep a country’s economy in check. But sometimes policies don’t work out as planned. Governments often take economic decisions that follow specific political agendas, and these decisions are not always beneficial for everyone.

Take, for example, a currency devaluation – the deliberate downward adjustment of the value of a country’s currency. This should, in theory, reduce the cost of a country’s exports and increase the international competitiveness of its goods. However, a currency devaluation can also impact consumers inside the country where it takes place.

We studied one such situation in 2015 where a currency devaluation affected the lives of consumers in the central Asian country of Kazakhstan. Our findings show that the currency devaluation made poor consumers poorer and wealthy consumers wealthier in relative terms.

Kazakhstan’s currency, the tenge, plunged after the government stopped managing the exchange rate in August 2015. The move was made in response to falling prices of oil (the country’s main export) and earlier devaluations by its two main trading partners, Russia and China.

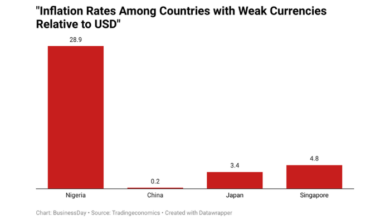

After one month, the tenge had lost 37% of its value against the US dollar, which increased to 56% after three months and 78.5% after six. This led to inflation far higher than the figures seen in the EU and the UK over the past few years.

A currency devaluation typically leads to inflation because foreign goods can become more expensive to import and, as a consequence, their prices in local currency might increase.

For our research, we looked at the consumer purchase records of a multinational retailer operating in Kazakhstan, as well as pricing records from its competitors. We found that product prices in the retailer’s stores increased by around 20% on average after the devaluation.

However, the effects were not equal across all consumer groups. Following the currency devaluation, wealthy consumers experienced a smaller effect on their cost of living compared to poorer consumers. The cost of living increased by 24% for poorer consumers compared to only 16% for rich consumers.

Our findings suggest that the retailer actually reduced its profit margins only for foreign products. In other words, they willingly decided to make less money on foreign products to ensure these goods were sold.

This may have been because the retailer wanted to keep hold of the customers who buy foreign products. In Kazakhstan, we determined this group of consumers to be largely wealthy people. The retailer, perhaps unsurprisingly, wanted to keep their most wealthy consumers happy as these people spend more money in their stores and purchase more expensive luxury products.

As a result, affluent consumers were hit with relatively lower price increases following the currency devaluation than poorer consumers. This pricing strategy, which is referred to as “pricing to market”, allows the retailer to preserve its market share.

By contrast, the retailer’s profit margin for local products remained relatively stable after the devaluation. Consumers of these products had to pay relatively more or switch to alternatives that were of a lower quality to cope with the price increases. The retailer looks to have passed the effects of the currency devaluation directly on to their poorer customers.

Wealthy consumers benefited not only from lower relative price increases following a currency devaluation. The variety of products they had access to changed by very little too.

This is because the retailer also replaced some of their local product offerings with foreign varieties. They possibly did so to further satisfy their richer customers who prefer foreign products. Already hit by higher relative price increases, poor consumers had fewer alternative products to choose from.

Burden falls on the poor

There are several takeaways from our findings. First, devaluing a country’s currency not only has consequences for its international standing, it can also have a large impact on domestic consumers. So, governments need to think carefully about both the external and internal consequences when tweaking the economy.

Second, currency devaluations can have a disproportionate effect on different economic strata of the population. A devaluation can, in some cases, raise the price of local goods which harms poorer consumers more than the rich.

Third, firms respond to the actions made by governments tactically. They are able to employ strategic pricing to the market and adjust their product offerings to maintain their competitive position and market share. But they do so often by disregarding the implications on the cost of living.

Above all else, our case study in Kazakhstan shows that consumers will often end up paying the price for drastic changes to economic policy. And the heaviest burden will fall on the poor.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source link